When we think about how alcohol affects mental health, we usually focus on the brain: neurotransmitters, dopamine, the hangover fog. But emerging research reveals that some of alcohol's most significant mental health effects happen somewhere unexpected—your gut.

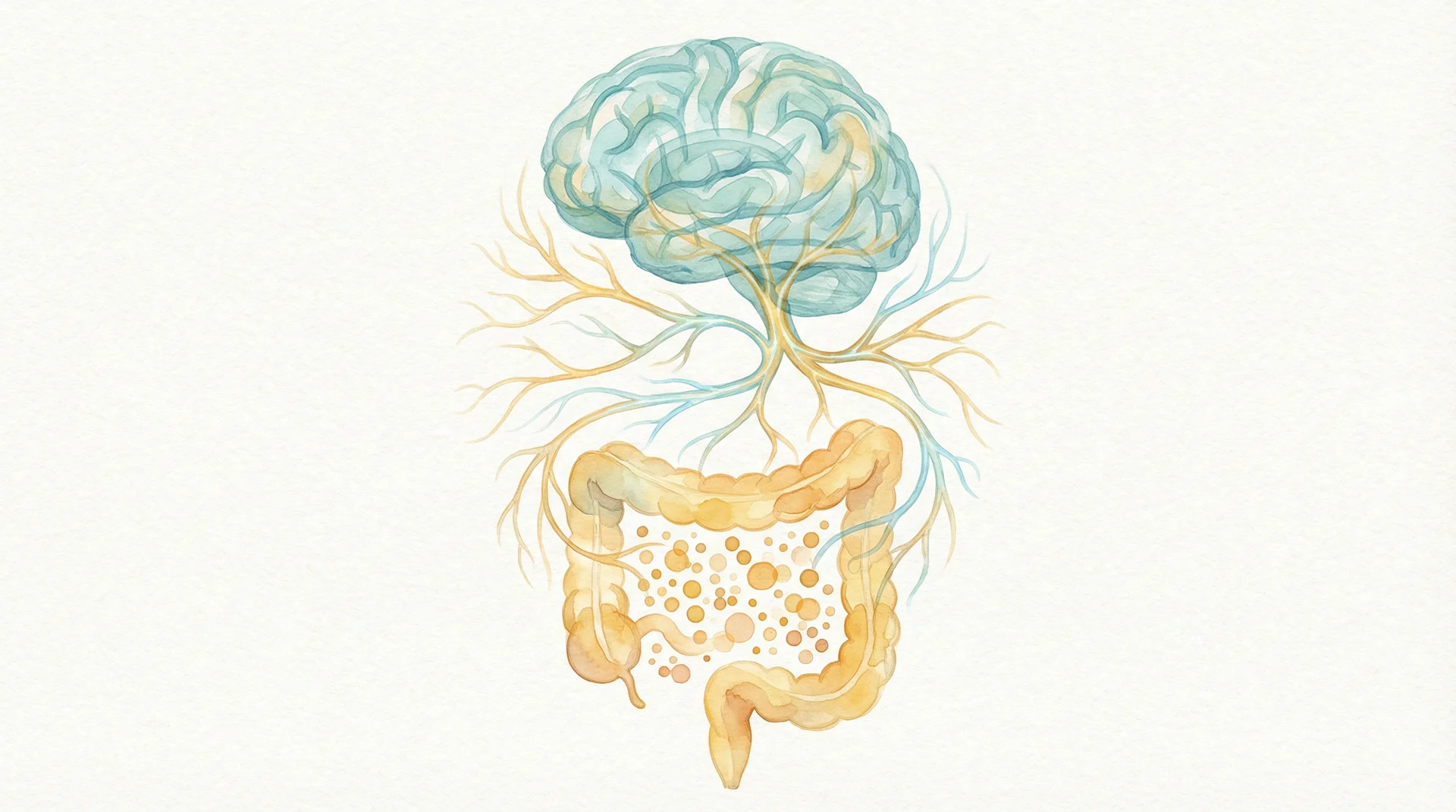

The gut-brain axis, as scientists call it, is a bidirectional communication highway between your digestive system and your brain. Your gut contains trillions of bacteria that produce neurotransmitters, regulate inflammation, and directly influence your mood, anxiety levels, and cognitive function.

Alcohol disrupts this system profoundly. Understanding how can help explain why drinking affects your mental health—and why stopping often brings psychological benefits that seem disproportionate to simply removing a substance.

Your Second Brain

Your gut contains about 500 million neurons—more than your spinal cord. This "enteric nervous system" can operate independently of your brain, earning it the nickname "the second brain."

But the gut doesn't just have its own nervous system; it's in constant communication with your actual brain through multiple pathways:

The vagus nerve is a direct physical connection running from your gut to your brainstem. It carries signals in both directions, allowing gut conditions to influence brain function and vice versa.

The immune system provides another communication channel. Your gut houses 70% of your immune cells. When gut health is compromised, immune activation sends inflammatory signals throughout the body, including to the brain.

Neurotransmitter production happens largely in the gut. About 95% of your body's serotonin—the "feel-good" neurotransmitter targeted by antidepressants—is produced in the digestive tract. Your gut bacteria also produce GABA, dopamine, and other mood-regulating chemicals.

The microbiome itself—the trillions of bacteria living in your gut—directly influences brain function through the compounds they produce and the signals they send.

This isn't metaphorical. The gut-brain connection is physical, measurable, and increasingly recognized as central to mental health.

How Alcohol Disrupts the Gut-Brain Axis

Alcohol affects the gut-brain connection through multiple mechanisms, each contributing to the mental health impacts many drinkers experience.

Microbiome disruption: Alcohol is antimicrobial—it kills bacteria. While this is useful for sterilizing wounds, it's problematic for your gut, where you need those bacteria. Regular drinking reduces microbial diversity and shifts the balance toward harmful bacteria. Studies show that even moderate drinking alters the microbiome composition.

The bacteria that suffer most are often the ones that produce beneficial compounds like short-chain fatty acids, which reduce inflammation and support brain health. The bacteria that thrive are often those associated with inflammation and disease.

Intestinal permeability: Alcohol damages the intestinal lining, creating what's colloquially called "leaky gut." Normally, your intestinal wall carefully controls what enters your bloodstream. When damaged, it allows bacteria, toxins, and partially digested food particles to leak through.

This triggers an immune response. Your body recognizes these substances as foreign invaders and mounts an inflammatory reaction. This inflammation doesn't stay local—it becomes systemic, affecting organs throughout the body, including the brain.

Neuroinflammation: When inflammatory signals reach the brain, they trigger neuroinflammation—inflammation of brain tissue. This has been linked to depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Studies show that people with alcohol use disorders have elevated markers of neuroinflammation. But even moderate drinking can increase inflammatory markers, particularly in the context of an already-disrupted gut.

Neurotransmitter disruption: With the gut bacteria that produce serotonin, GABA, and dopamine compromised, the supply of these crucial neurotransmitters is affected. This may partly explain why regular drinkers often experience mood disturbances even when they're not actively drinking.

The Anxiety Connection

Many people drink to relieve anxiety, but alcohol ultimately makes anxiety worse—and the gut-brain axis helps explain why.

In the short term, alcohol enhances GABA activity in the brain, producing a calming effect. But this is borrowed calm. Your brain compensates by reducing its own GABA production and increasing excitatory neurotransmitters. When the alcohol wears off, you're left with an overactive, under-calmed nervous system—the classic "hangxiety [blocked]."

But there's a gut component too. Alcohol-induced gut dysbiosis (microbial imbalance) is associated with increased anxiety in both animal and human studies. The inflammatory signals from a damaged gut activate stress pathways in the brain. And reduced gut production of calming neurotransmitters like GABA and serotonin leaves you more vulnerable to anxiety.

This creates a vicious cycle: you drink to calm anxiety, alcohol damages your gut, gut damage increases anxiety, you drink more to cope.

The Depression Connection

The gut-brain axis also helps explain alcohol's relationship with depression.

Serotonin, often called the "happiness neurotransmitter," is primarily produced in the gut. When alcohol disrupts the bacteria responsible for serotonin production, mood suffers. Studies have found that people with depression have different gut microbiome compositions than those without—and that alcohol use disorder is associated with similar microbial patterns.

Inflammation is another link. The "inflammatory theory of depression" suggests that chronic inflammation contributes to depressive symptoms. Alcohol-induced gut permeability and the resulting systemic inflammation may be one pathway through which drinking contributes to depression.

This doesn't mean alcohol causes all depression, or that fixing your gut will cure depression. But for many people, alcohol is making their depression worse through mechanisms they're not aware of.

What Happens When You Stop

The encouraging news is that the gut-brain axis can heal when you remove alcohol from the equation.

Microbiome recovery: Studies show that gut bacteria begin recovering within days of stopping drinking. Beneficial species start repopulating. Diversity increases. The balance shifts back toward health.

A 2023 study found that people who stopped drinking showed significant improvements in microbiome composition within two weeks, with continued improvement over months.

Gut healing: The intestinal lining can repair itself relatively quickly when the damaging agent is removed. Reduced permeability means fewer inflammatory triggers entering the bloodstream.

Inflammation reduction: As gut health improves and inflammatory triggers decrease, systemic inflammation drops. This includes neuroinflammation, which may partly explain the improved mental clarity and mood stability many people report after stopping drinking.

Neurotransmitter normalization: With gut bacteria recovering, production of serotonin, GABA, and other neurotransmitters can normalize. This takes time—weeks to months—but many people report gradual improvements in mood and anxiety.

Supporting Your Gut-Brain Recovery

If you're reducing or stopping alcohol, you can support gut-brain healing through several evidence-based strategies:

Eat fermented foods: Yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and other fermented foods contain beneficial bacteria that can help repopulate your gut. Aim for a serving or two daily.

Increase fiber intake: Fiber feeds beneficial gut bacteria. Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes provide the prebiotic fiber your microbiome needs to thrive.

Reduce processed foods: Highly processed foods, artificial sweeteners, and emulsifiers can harm gut bacteria. Whole foods support a healthy microbiome.

Consider probiotics: Probiotic supplements may help, though the research is mixed. Look for strains with evidence for mental health benefits, such as certain Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species.

Manage stress: Chronic stress damages the gut lining and disrupts the microbiome. Stress management practices [blocked] like meditation, exercise, and adequate sleep support gut health.

Be patient: Gut healing takes time. Most people see significant improvement within a month, but full recovery may take several months.

The Bigger Picture

The gut-brain connection adds another dimension to understanding why alcohol affects us the way it does—and why stopping often brings benefits that seem to exceed simply removing a substance.

When you stop drinking, you're not just giving your liver a break. You're starting a week-by-week healing process [blocked] that affects your entire body. You're allowing an entire ecosystem inside you to recover. You're reducing inflammation throughout your body. You're restoring the communication pathways between your gut and brain.

This is why many people report that stopping drinking improved their mental health more than they expected. It's not just about removing alcohol's direct effects on the brain—it's about healing a system that touches everything.

The Bottom Line

Your gut and brain are intimately connected, and alcohol disrupts that connection at multiple levels. It damages gut bacteria, increases intestinal permeability, triggers inflammation, and impairs neurotransmitter production—all of which affect your mental health.

The good news is that this system can heal. When you stop drinking, your gut begins recovering within days, with cascading benefits for inflammation, neurotransmitter production, and brain function.

If you've been drinking regularly and struggling with anxiety, depression, or brain fog, your gut may be part of the story. And healing it may be part of the solution.

Your gut health journey starts with your first clear day. Download ClearDays to track your progress and notice how your mood and mental clarity improve as your body heals.